Read This, Not That--Criminal Justice

Discourse dissection, the Lindy effect, and a belated review of a classic

If you diet, invest, and think according to what the "news" advocates, you'll end up nutritionally, financially, and morally bankrupt.

Naval Ravikant

Inputs matter. In trying to understand a topic as complex and dynamic as criminal justice, books hold a coveted place at the top of the input hierarchy. At least that’s how it should be. Posts have a point of view, articles have an argument, studies have analysis—but they don’t provide scope and scale. Books take time, develop theses, challenge different contrary opinions, surface and interpret data, and have editorial oversight. Books are built to inform, challenge, and endure.

There’s even a term for the endurance of a valued book—the Lindy Effect. According to Nassim Nicholas Taleb:

“If a book has been in print for forty years, I can expect it to be in print for another forty years. But, and that is the main difference, if it survives another decade, then it will be expected to be in print another fifty years. This, simply, as a rule, tells you why things that have been around for a long time are not ‘aging’ like persons, but ‘aging’ in reverse. Every year that passes without extinction doubles the additional life expectancy. This is an indicator of some robustness. The robustness of an item is proportional to its life!”

Negative space is artsy term for the area not covered by the subject of any work. Skilled creators use that space to inform or interpret the subject or other matters. Biased creators refuse to contend with uncomfortable facts or ideas and treat the negative space like a black hole where all the real interesting ideas go. The negative space in this substack is the lack of any real discussion of books on criminal justice. We talk about reforms, laws, referendums, reports, articles, posts, datasets/charts, institutions, judicial opinions, interviews, trends, impacts, surveys, and even crazy crimes of the week. Almost none of this input comes from books. It’s not that there aren’t plenty of books, that we haven’t read them, or even that we don’t have draft reviews of them stacked in a virtual folder but the truth is we haven’t posted any book reviews here because contemporary books about criminal justice suck.

We’ve found no real value in discussing the substance of these books, which are about the otherwise interesting topics of mass incarceration, community corrections, criminal justice reforms, plea bargaining, sentencing, process as punishment, etc. But there may be value in showing how to easily spot one of these vanity projects and save yourself hours of time.

The first thing to know is that they will all have good reviews and they will come from a person with the appropriate degree or experience. You can’t identify these books by their covers. The trick is to pick out the bad book clichés. Like the cliche’s in teen books (absent parents, the “chosen one,” the sorting of the teens, the love triangle), these books have their own repetitive language. Once you see them, they can’t be unseen. Be on the look out for:

a foreward that is about the author, not the subject.

an author with primary ties to Foundations/NGOs/Nonprofits.

an ideological point of view that would never offend a Foundation, NGO, or Nonprofit.

Personal war stories over data or insight.

Obligatory anecdotes that introduce each chapter to humanize the argument. (These actually just reveal the weakness of an argument while buffing the word count).

All the anecdotes are about a person mistreated by the system with no discussion of crime victims.

Lies about the author’s ignorance or incuriosity. This is a strange one, but you might find a criminal law professor suggesting that they don’t really understand civil asset forfeiture or an advocate in criminal justice may claim they never considered the impact of probation or parole. Maybe they do this to seem relatable to the reader, but it really just makes them seem like liars.

a thesis that is only addressed in 10% of the book. (This is proof that the title is just marketing).

Repeated framing that systems rather than people are responsible for crime and criminal justice but only prisons (not schools) need reforms.

In short, if you can’t find a single argument to challenge the priors of a faculty luncheon at Harvard, your time may be better spent elsewhere.

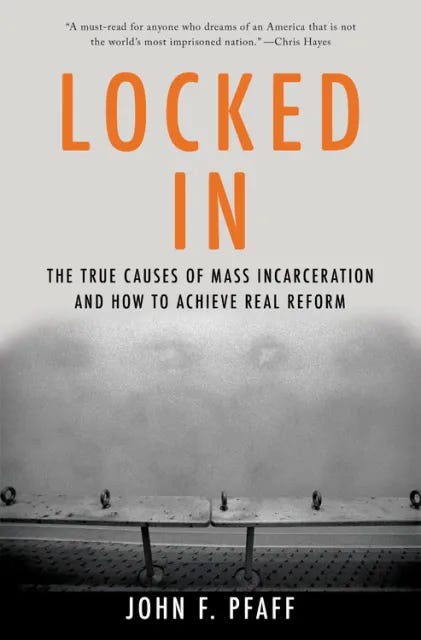

But where? There must be exceptions. Luckily, there are. And you only have to go back to 2017. John Pfaff’s “Locked In,” is a modern classic jammed with useful data and challenging ideas across several different dimensions of incarceration.

While a progressive himself, Pfaff is not afraid to bust persistent myths held by the left and the right. Using actual data, he tackles Trump and criminal justice reform, whether low level drug convictions actually fill the jails and prisons, and the limited role of private prisons. The book also provides a clear-eyed evaluation of the the out-sized role and carceral incentives of public sector unions, the impact of sentence length, that there is not one but actually thousands of criminal justice systems across the US, and the real costs of mass incarceration.

Beyond the reality check for the system as it stands, Pfaff outlines actual potential solutions including reframing the reform debate around easy wins for low-level crimes, increasing funds for defense counsel, improving data and data transparency, reforming plea bargaining tactics, reconsidering incentives between county officials and state prison responsibilities, assessing and adapting electoral incentives, and funding alternatives to prison.

If there is one game changer in the book, it’s Pfaff’s argument highlighting the central role that prosecutors play in mass incarceration (and not for reasons you might think). This argument has generated thoughtful criticism, a response from Pfaff, and is ripe for a new analysis given the current data from the progressive prosecutor movement over the past decade.

“Locked In” is robust, still current and enduring. It has Lindy. May there be many more like it.